Wittgenstein's Tractatus: Now With Examples

[Copied over from my old blog]

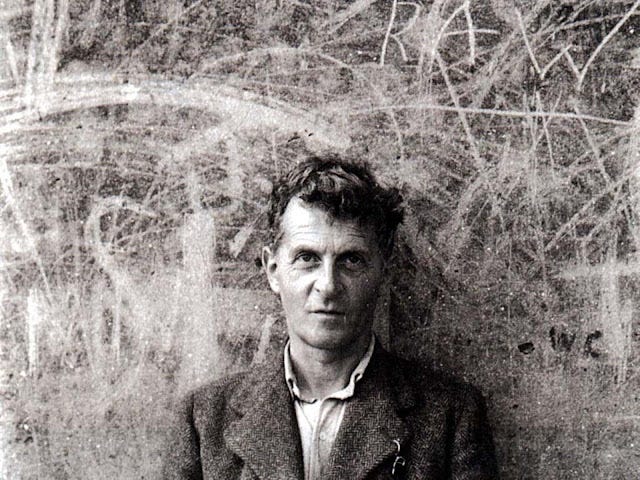

Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus is a century-old this year. It deserves its reputation as one of the most difficult books in modern philosophy.

Part of the difficulty is down to its subject matter. The book is about how language represents reality: how sentences like ‘The cat is on the mat’ manage to tell us something about the world. Exactly because we’re so accustomed to using these kinds of sentences, it can be hard to grasp just what Wittgenstein’s worry is. We’re like fish reading a book about the nature of water.

Another part of the difficulty can be chalked up to self-reference. Wittgenstein uses language to conduct his investigation into the nature of language. The book is thus a kind of ouroboros eating its own tail, with all of the trouble that involves.

A third part of the difficulty stems from the book’s length. It’s just 80 pages of cryptic, tweet-length remarks – sometimes precise, sometimes vague – covering everything from metaphysics to logic to ethics to theology.

But at least part of the difficulty is down to Wittgenstein’s stubborn refusal to give any examples of the kinds of things he’s talking about: names, objects, elementary propositions, atomic facts. His reluctance is understandable in a way. Wittgenstein claimed to establish the existence of these things on a priori grounds – via argument, rather than observation – and he thought that any examples he could give would be misleading. But his reluctance is peculiar in another way. As we’ll see, Wittgenstein is willing to write things that aren’t strictly true in order to help us understand him, so it’s strange that he didn’t extend this willingness to concrete examples and illustrations.

In this post, I’m going to do what Wittgenstein didn’t. I’m going to give a quick overview of the Tractatus that’s chock-full of examples and analogies. My exposition will be rough at some points and simplistic at others. Readers looking for maximum accuracy should consult the academic secondary literature. I’m writing this post because even the so-called ‘Introductions’ to the Tractatus can be hard-going.

Let’s begin. Wittgenstein’s main concern in the Tractatus is with propositions. Propositions are those things that can be true or false, the kinds of things that we express with declarative sentences. ‘The cat is on the mat’, for example, is a declarative sentence expressing the proposition that the cat is on the mat.

Some propositions have sense. Roughly, they tell us something about the world. More precisely, whether they’re true or false depends on how the world is arranged. ‘The cat is on the mat’ expresses a proposition with sense. It’s true if the cat is on the mat and false otherwise. Other propositions are senseless. They’re true no matter how the world is arranged, so they tell us nothing about the world. ‘Either it’s raining or it’s not raining’ expresses a senseless proposition. Still other propositions are nonsense. They also tell us nothing about the world, but not because they’re true no matter what. Instead, they tell us nothing because they’re neither true nor false. ‘Colourless green ideas sleep furiously’, for instance, expresses a nonsense proposition. Or, to take one of the rare examples in the Tractatus, ‘The good is more identical than the beautiful’ expresses a nonsense proposition.

These cases are pretty clear-cut, but others are less certain. Does the proposition expressed by ‘Murder is wrong’ have sense? Does it tell us anything about the world? How about the proposition expressed by ‘Time isn’t real’? Does that have sense? We can argue about each of these propositions individually, but that can be a long and tedious affair. It would be convenient if we had some formula to tell us which propositions are sensical, which are senseless, and which are nonsensical.

The Tractatus gives the outlines of such a formula. It presents ‘the general form of proposition’: a recipe for constructing propositions with sense. Wittgenstein’s claim is that all sensical propositions are of this same general form. Any proposition not of this form is nonsense. Wittgenstein is thus trying to do philosophers a huge favour. In philosophy, talking nonsense is an occupational hazard. You might well come to the end of a long career only to discover you were talking nonsense the entire time. The Tractatus is supposed to help us avoid that fate.

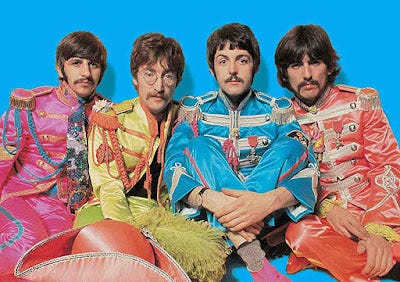

To see how Wittgenstein unearths ‘the general form of proposition’, let’s start with a particular example. Take the proposition expressed by ‘One of the Beatles was a bachelor.’ This proposition is sensical. It tells us something about the world. This proposition can also be analysed, by which I mean it can be broken down into parts. ‘One of the Beatles was a bachelor’ can be analysed into four propositions, connected by the word ‘or’: (1) John was a bachelor, or (2) Paul was a bachelor, or (3) George was a bachelor, or (4) Ringo was a bachelor. The symbol ‘bachelor’ can also be analysed, this time into two symbols connected by the word ‘and’. A bachelor is (1) unmarried, and (2) a man.

This process of analysis might well continue, but it can’t go on forever. Eventually, we’ll reach what Wittgenstein called elementary propositions: propositions that can’t be broken down. These elementary propositions are combinations of names: symbols that can’t be broken down.

Since our example proposition – One of the Beatles was a bachelor – has sense, each of its elementary propositions must also have sense. For these elementary propositions to have sense, each of the names in these elementary propositions must refer to something. The proposition expressed by ‘London is in England’ has sense because each of its terms refers to something. The proposition expressed by ‘London is in Flobertness’ is nonsensical, because ‘Flobertness’ doesn’t refer to anything. Wittgenstein thus concludes that names must refer to simple objects. These objects can’t be broken down. If they could be broken down, they might cease to exist. Then the corresponding name would have no reference, and any elementary proposition featuring that name would be nonsense. Wittgenstein’s enquiry into the nature of language has thus led him to a conclusion about the nature of reality: there must be simple objects forming the substance of the world.

Wittgenstein gives us no examples of objects, names, or elementary propositions. He establishes their existence through argument rather than observation, and so is happy to let others do the work of identifying them. He thinks that he can know that objects, names, and elementary propositions exist, even in the absence of examples. Think of it this way. I can know that you have an ancestor who spent their entire life underwater, even though I can’t point out any such ancestor. Take your parents and ask, ‘Did one of them spend their entire life underwater?’. If the answer is – as I suspect – ‘No,’ then take your parents’ parents: did one of them spend their entire life underwater? That’ll also be a ‘No,’ so take your parents’ parents’ parents, and so on. Eventually, the answer must be ‘Yes,’ because we all descended from sea creatures. I can thus know that you have at least one entirely aquatic ancestor, even though I know of no examples. Wittgenstein’s argument is analogous: if a proposition has sense, its analysis must end with elementary propositions made up of names referring to simple objects. Never mind that examples are hard to come by.

All that said, here’s one way of illustrating Wittgenstein’s view. Let the fundamental particles of matter – quarks, leptons, and the like – be our objects. Each such object is assigned a number, which serves as its name. Elementary propositions are then combinations of numbers. We might express them with lists, like ‘13, 28, 567, 435.’

(This illustration isn’t entirely faithful to the theory expressed in the Tractatus. Wittgenstein’s objects can’t be divided. They’re ‘unalterable and subsistent,’ and they exist in every world that we can imagine. Fundamental particles might lack some of these properties.)

Note that elementary propositions are just combinations of names, like ‘13, 28, 567, 435.’ They don’t say ‘28 is between 13 and 567’ or ‘567 crashes into 435’ or anything like that. How then can elementary propositions have sense? How can a mere combination of names tell us something about the world?

Wittgenstein’s answer is given by his famous picture theory of meaning. It’s an idea that’s said to have occurred to him in a Paris traffic-court, where he saw an accident reconstructed with toys. Those toys stood as proxies for the people and cars involved in the accident, and the way that the toys were arranged showed the way that the people and cars were arranged at the time of the accident. The toys together constituted a picture: ‘a model of reality.’ Wittgenstein claims that elementary propositions are also a kind of picture: an elementary proposition is a picture of an atomic fact. An atomic fact is a combination of objects, an elementary proposition is a combination of names, and the way that the names are combined in an elementary proposition shows how the corresponding objects are combined in an atomic fact.

With that last sentence, we’ve completed our descent from the top – an ordinary proposition expressed by ‘One of the Beatles was a bachelor’ – down to the very bottom: names, objects, elementary propositions, and atomic facts. Now to climb back up again. Wittgenstein’s claim is that all propositions with sense are founded on elementary propositions. More precisely, each proposition with sense is a truth-function of elementary propositions. To understand what’s meant by ‘truth-function,’ return to our Beatles example. The proposition expressed by ‘One of the Beatles was a bachelor’ is a truth-function of the following four propositions: (1) John was a bachelor, (2) Paul was a bachelor, (3) George was a bachelor, (4) Ringo was a bachelor. What that means is that the truth of ‘One of the Beatles was a bachelor’ depends only on the truth of the latter four propositions. Once you know whether each of the latter four propositions are true, you know whether ‘One of the Beatles was a bachelor’ is true. More generally for Wittgenstein, if you know the truth of all the elementary propositions, you know everything there is to know.

That gives us Wittgenstein’s formula for determining whether a proposition has sense. If a proposition could be true or false, depending on the truth of elementary propositions, that proposition has sense. If a proposition is true no matter which elementary propositions are true, that proposition is senseless. And if a proposition is not a truth-function of elementary propositions – if you couldn’t tell whether it’s true or false even if you knew all the elementary propositions – that proposition is nonsense.

This formula turns out to be bad news for philosophers. In Wittgenstein’s estimation, only scientific questions can be given answers with sense. The propositions of ethics (like ‘Murder is wrong’), aesthetics (like ‘Paris is beautiful’) and theology (like ‘God exists’) turn out to be nonsense. Indeed, all philosophical propositions turn out to be nonsense.

But hang on a minute! The Tractatus is filled to the brim with philosophical propositions. Does Wittgenstein think he’s been writing nonsense this whole time? Funnily enough, yes:

My propositions serve as elucidations in the following way: anyone who understands me eventually recognizes them as nonsensical, when he has used them—as steps—to climb up beyond them. (He must, so to speak, throw away the ladder after he has climbed up it.) He must transcend these propositions, and then he will see the world aright. – 6.54

But this answer only invites more questions: what’s the point of reading the Tractatus? How can a book full of nonsense help us ‘see the world aright’?

Wittgenstein’s answer is as follows: the Tractatus shows that any attempt to answer philosophical questions must be nonsense. There simply are no sensical answers to such questions. And so, in the words of Wittgenstein’s final proposition, ‘What we cannot speak about we must pass over in silence.’

But here one might object. Even if Wittgenstein’s propositions imply their own nonsensicality, that doesn’t prove that all philosophical propositions are nonsense. It doesn’t even prove that Wittgenstein’s propositions are nonsense. They might just be plain-old-false. Consider an analogy. The sentence ‘Any sentence consisting of more than five words is nonsense’ implies its own nonsensicality. But that sentence isn’t nonsense. It’s false.

Clearly, Wittgenstein didn’t think that his propositions were false. What might justify his own, more radical reading? Here’s one answer. Suppose that the propositions of the Tractatus strike us as the only viable answers to philosophical questions even after we recognise that these propositions imply their own nonsensicality. Then we might conclude that all philosophical propositions must be nonsense.

I’ll end with a metaphor. Imagine you’re in a clearing in a South American rainforest, searching for El Dorado. Many paths are open to you, and you don’t know which will take you there. You choose a path that looks promising, but after travelling a while you realise that you’re back where you started. You resolve to try again. But even knowing that the first path leads you back to the clearing, it still strikes you as the only way to reach your destination. In that case, you might conclude, there’s no need to try another path. There is no El Dorado.